Article

The New Labour Codes Deliver a Mixed Bag of Assurances

Iqbal Tahir comments on the newly approved labour codes by the Indian parliament.

-

Iqbal Tahir

Iqbal Tahir

(I) Introduction

The Indian Parliament’s recent approval of three labour codes – the Industrial Relations (IR) Code, 2020; the Code on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (OSHWC), 2020; and the Code on Social Security (SS), 2020 – is expected to simplify the complex maze of existing labour laws, enable a more conducive business environment, and boost employment and economic activity. With the passage of these three codes (now bills), the government has demonstrated its seriousness to dispense with multiple and outdated laws which are not only incompatible with modern business environments but also give rise to inconsistencies and ambiguity.

On the one hand, the new labour codes are expected to bring about a higher level of regulatory compliance, give industries/businesses greater flexibility and simultaneously protect workers’ rights and benefits. On the other, they are also being seen as enablers to boost India’s ranking in the Ease of Doing Business index and attract higher inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI). The three new codes, along with the Code on Wages, 2019 (passed in August 2019), are the culmination of years of effort to streamline and consolidate over 100 state and 40 central labour laws regulating various aspects of labour.

In 2002, the second National Commission on Labour (NCL) [set up in 1999 by then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee] recommended the consolidation of multiple central and state labour laws into four or five codes since existing legislations were “complex, with archaic provisions and inconsistent definitions.” For the next decade or so, the recommendations remained on paper. In 2014, the threads were picked up again and steps were taken to consolidate multiple central labour laws into four codes. In 2019, after being introduced in Parliament, the codes were referred to the Standing Committee on Labour which suggested 100 changes, of which 74 were accepted in the final draft.

(II) Details of the Labour Codes

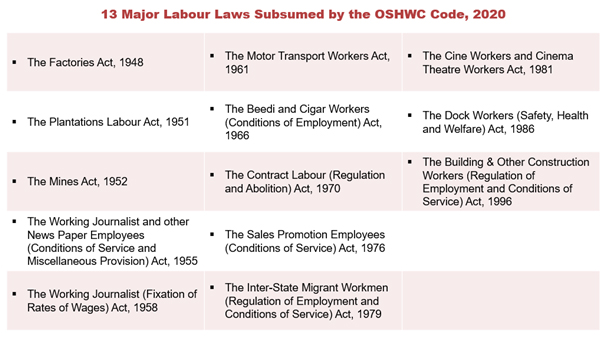

The OSHWC code subsumes and replaces 13 centrallabour laws – relating to safety and health standards, working conditions, employee welfare provisionsand other associated matters – into a single code.

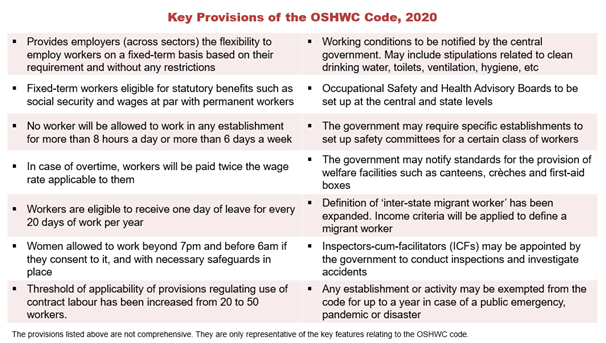

The OSHWC codeapplies to establishments employing at least 10 workers, and to all mines, docks and establishments undertaking any hazardous or life-threatening activities (to be notified by the central government). Under the code, the government has allowed the use of a single licence by firms to hire contract workers across different locations instead of the previous requirement of multiple licences.Some of the other key provisions of the OSHWC code include the following:

(III) Analysis

While the intent of the OSHWC code is laudable, it excludes large areas from its scope. Moreover, the code leaves room for a high level of ambiguity since no minimum standards have been clearly specified; instead, central and state governments have been empowered to stipulate such standards through notification.

The OSHWC code does not apply to large sections of the economy, prominent among which is the agricultural sector (where occupational safety, health and working conditions are unregulated). It excludes from its scope establishments employing less than 10 workers as well as informal workers employed in organized sectors such as e-commerce and IT/ITeS. Considering that establishments employing 10 or more workers comprise a minuscule proportion of total establishments (as per the Sixth Economic Census), it results in an overwhelming majority of the working population being excluded from coverage under the OSHWC code.

Another key shortcoming of the OSHWC code is that it does not specify any minimum standards with respect to health, safety and working conditions, nor does it make employers responsible with respect to safety and health. In a move which increases the potential for political manoeuvring, the central government (and, in some cases, state governments) has been empowered to stipulate such standards through notification. Given that labour laws were being completely overhauled, clearly specifying minimum standards for occupation, safety and health in the code itself would have removed ambiguity and benefited both employers and workers.

The setting up of a safety committee is applicable only to those establishments which employ more than 250 workers. The efficacy of this provision is also questionable since the unorganized sector comprises establishments which are self-owned (employing limited or no external workers) or which employ only a limited workforce (significantly lower than the threshold of 250). This effectively means that workplace safety measures will be inapplicable to over 90% of India’s workforce, which is a serious matter considering that an estimated 48,000 work-related deaths take place in India every year.

Despite several shortcomings, the OSHWC code marks a progressive step to streamline and reform India’s archaic labour laws and bring them in sync with modern business requirements. However, the code should incorporate clear and specific provisions so that there is no room for ambiguities or multiple interpretations.

The OSHWC code incorporates several progressive features. By mandatorily requiring industrial establishments to provide washrooms, bathing facilities and locker rooms for men, women and transgender workers, the code marks a big step forward in recognizing the rights of transgenders. It also prohibits employers from knowingly hiring women employees in any establishment during the six weeks immediately after the day of their delivery, miscarriage or medical abortion. The expansion of the definition of ‘inter-state migrant worker’ and recognition of the rights of contract workers are also positive steps, particularly in light of the extreme distress faced by these workers during the coronavirus pandemic.

In many quarters it is being viewed that the new labour codes, including the OSHWC code, have been framed keeping in mind the interest of employers without sufficiently addressing the health, safety and working conditions of millions of workers, especially those operating (or employed in) micro and small establishments. By leaving many provisions open-ended and without clear definitions or minimum standards, the government has left enough scope for ambiguities and multiple interpretations. To be completely effective, the labour codes must incorporate clear and specific provisions in relation to these matters. Most importantly, the codes need to consider ground realities and reframe their provisions accordingly so that they are able to provide universal coverage to all sections of the working population.

- FIR Copy of Mahatma Gandhi assasination case

- Licito Concurso'20

- Rules for Licito Concurso '20- A National Legislative Drafting Competition

- Registration Form for Licito Concurso-20

- www.apexcourtweekly.substack.com

- www.lawupdater.com/wp/

- XIIIth K.K. Luthra Memorial Moot Court Competition 2017

- President of India Presented with the First Copy of the Book Statement of Indian Law Published by Thomson Reuters