Article

Agricultural ‘Liberalisation’ Reforms: The New Farm Bills And The Impact On Farm Income

Yash Jain comments on the impact of the new farm bills on farm income.

-

Yash Jain

Yash Jain

Indian agriculture, with its allied sectors, is indisputably the largest livelihood provider in India. For decades now, agriculture has remained the backbone of the Indian economy by contributing around 17 per cent to the GDP and engaging either directly or indirectly, around 60 per cent of the population.1 Indian agricultural sector has performed well over the last two decades by uninterruptedly producing surplus food grains, including the record high production of 292 million tonnes of food grains in 2019-20.2 Today, India is not only a self-sufficient country in terms of food grains but also among one of the highest producers of grains like wheat and rice. The agricultural sector is functioning at its pinnacle, while also exporting large amounts of food grains. However, farmers income is not gearing up with the same pace of increased production. From 2004-05 to 2011-12, farmers’ income grew at a meagre rate of 3.94 per cent per annum, and it took around 18 years for the income to double in real terms.3 The year 2019 was the worst year for farmer incomes in the last 20 years, though the NITI Aayog, the foremost think-tank of the country, has come up with realising the goal of doubling the farmer's income by 2022.4 The goal remains a distant reality.

2. Press Note on National Conference of Kharif Crops 2020, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, (16 April 2020) <https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=1614994> accessed 22 October 2020.

3. KJS Satyasai, “Farmers’ income: trend and strategies for doubling” [2016] 71 Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics 3.

4. NITI Aayog, ‘Doubling Farmer’s Income: Rationale, Strategy: Prospects and Action Plan’ (2017) NITI Policy Paper No 1/ 2017, <https://niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document_publication/DOUBLING%20FARMERS%20INCOME.pdf> accessed 29 October 2020.

In pursuance to uplift the current scenario and improve the market situation, the government has passed two significant Bills, namely, Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020, and Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020 and an amendment to the Essential Commodities Act, 1955. These reforms are being termed as the ‘agricultural liberalisation’ reforms, much like the illuminating 1991 ‘economy liberalisation’ reforms. Nevertheless, these reforms have caused an uproar in the country, including protests from the farmer community. The subsequent sections will deal with the elucidation of these reforms and their impact on the farmers’ income.

MARKET STRUCTURE AND THE NEW AGRICULTURAL BILLS

The latest Bills have been both welcomed and unwelcomed by different sections of people. Let us look through the modalities of the Bills and analyse the stance of the government to liberalise the market and in turn, increase the farmer's income.

Until now, the agricultural markets in the country were mainly controlled by the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (“APMC”). These committees, which were established in many parts across the country, regulated the trade between the farmers’, traders and the buyers by providing licenses to the buyers and the traders to ensure just and fair trade. APMC's also levied market fees and other charges on the farmers' produce and in return, facilitated the farmers with the required infrastructure and platform to sell their harvest.

The APMC model was conceptualised to ensure an effective and efficient trade in the agricultural sector, but over time, the model has not fulfilled the required objective. There were very few licensed traders, and buyers in most of the APMC's which led to the cartelisation of the market and the farmer had to agree to the price as offered by these traders. Also, a farmer registered with a particular APMC could only sell the produce in that APMC and even if he/she is offered a high price at any other APMC, then also he/she was not entitled to deal in that APMC mandi. Further, the farmers had a minimal number of buyer base, as the role of private players were very limited, and the entry into an APMC was a herculean task. Therefore, the APMC model was not very well executed, and it was high time for the government to alter the existing agricultural market structure, as a well-structured market is a key requirement for raising farm income.5 The changes to the markets have been brought in through the following Bills.

The Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020

As mentioned earlier, the farmers were bound to the particular APMC mandi, but the present Bill demolish the market boundary and allows intra and inter-state trade which could be done in any market across the country.6 Further, the Bill brings in technology to the sector by introducing electronic trading to facilitate online buying and selling and opening up the market for the companies and private entities to operate on such platforms.7 The abolition of collection of any kind of market fee from the farmer is another major breakthrough provided through this Bill.8

6. The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020, s 3-4.

7. ibid, s 6.

8. ibid.

The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020

This Bill formalises ‘contract farming’, where there could be a prior contract between the farmer and the buyer before the crop season.9 In the case of contract farming, the price of the product would be decided in the contract itself, though there could be variation clause in the agreement, the method of price determination would be priorly decided. The Bill also provides for a fair and balanced dispute settlement procedure, in case any dispute arises.10

The Essential commodities (Amended) Act, 2020

This Act gave the government the power to regulate certain commodities which were designated as “essential commodities”. Earlier, the central government could regulate such commodities at their will, but the amendment has now limited the government intervention to only ‘extraordinary circumstances’, including war, famine, extraordinary price rise and natural calamity.11 Further, until now, the farmers were bound by a stock limit where they could not reserve the food grains above a certain limit. This amendment relaxes government intervention which now could only impose stock limits when there is a 50% increase in the retail price of non-perishable agricultural items and 100% increase in the retail price of perishable farm items.

These radical Bills aims to liberalise the sluggish agricultural market and make it more efficient. These Bills are introduced with the intent to open up the market and provide a more significant opportunity for the farmers to sell their produce. But, will the new reforms result in an increase in farm income?

10. Ibid, s 13-15.

11. The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020, s 3(1)(A).

FARM INCOME

Current farm income

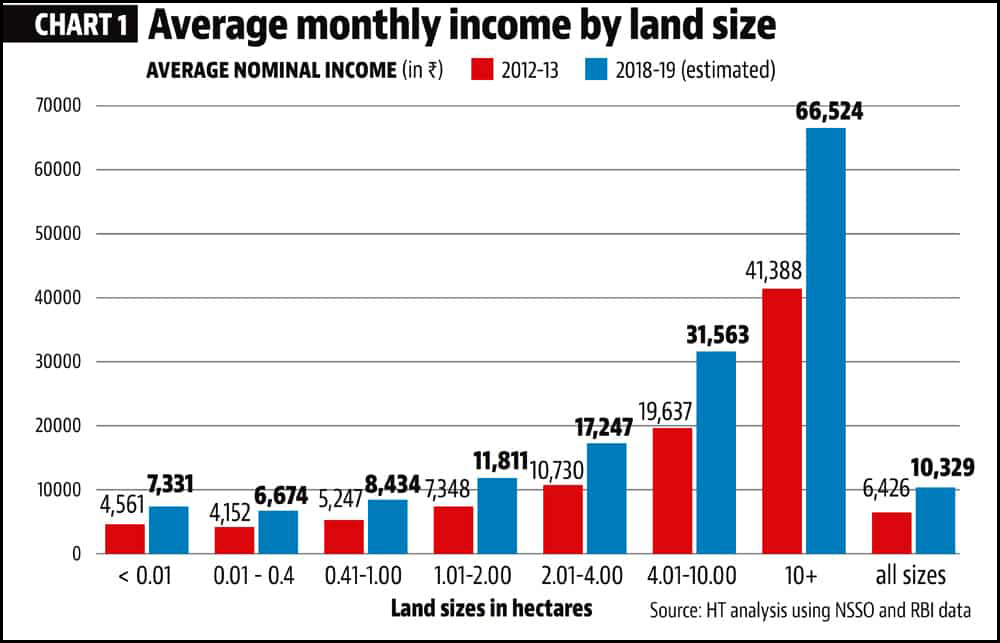

Until now, India’s primary focus for the development of the agricultural sector has been raising the farm output and improving food security.12 The government has been quite successful in raising the production as mentioned earlier, and the food security requirement is also worked upon. However, no strategy recognised the need to increase farm income. As a result of this weary policies, the average monthly income per agricultural household from all sources is looming just Rs. 6,426 (the latest official data from NSSO are based on the Situation Assessment Survey of Agricultural Households conducted in 2013).13 Following the current growth rate, the estimated income of the farmers would still be Rs. 10,329 only per month.14 Also, this is the average income, including the big and marginal farmers of all status and all type of landholdings. Perplexingly, if we only see the average income of all farmers owning up to 2 hectares of land, then the average monthly income would come out to even less, which is, Rs. 5,240.15 These farmers, according to NSSO, accounts for 86% of the total agricultural households in India.16 More shockingly, as per NITI Aayog, 80 per cent of the poor in rural areas are dependent on farming.17 The bulky stats and figures more or less define the conditions of the despair farmers and is a clear indicator that present situations need upliftment, to not just improve the Production but also add something to the farmer's income.

13. MoSPI, National Sample Survey Organisation, ‘Key Indicators of situation of agricultural households in India in 2013’ (December 2014) <http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/KI_70_33_19dec14.pdf> accessed 26 October 2020.

14. Abhishek Jha, ‘Rs 6,000 is 6% of a small farmer’s annual income, according to NSSO data’ (Hindustan Times, 6 February 2019, <www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/rs-6-000-is-6-of-a-small-farmer-s-annual-income-according-to-nsso-data/story-rddMw0hk6cSbxjo7E1GyKK.html> accessed 24 October 2020.

15. ibid.

16. MoSPI, National Sample Survey Organisation, ‘Income, Expenditure, Productive assets and Indebtedness of agricultural households in India in 2013’ (December 2014) Report No. 576 <http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/nss_rep_576.pdf> accessed 26 October 2020.

Increase in production but not in Farm income?

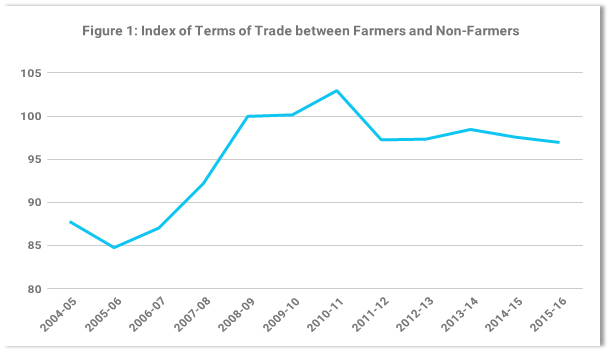

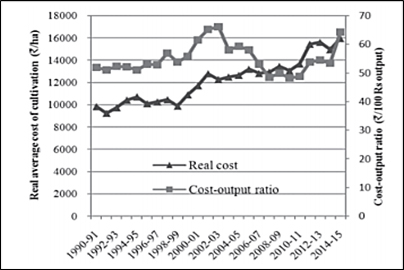

The income of farmers seems to be mounting due to the increased cash flows, especially in rural areas owing to good rainfall in past years. But these increase in income does not appear widespread as on real terms the trend of farmer income has been declining since 2011-12.18 Further, crop sector contribution to the real GVA was also on the back seat during 2014-2018, growing just 0.5 per cent during the period.19 Only horticulture and allied activities have shown some growth, while a decline has been observed in other crop production. The declining growth of the GVA is the least due to the weather conditions, which were agriculturally favoured in the last few years. But this decline can be attributed to the rising input costs and in turn, falling profits. The rise in the cost of production includes bulging petroleum prices which lead to higher irrigation costs and transportation costs.

18. ibid.

19. Ministry of Economic Affairs, ‘An overview of India’s economic performance in 2017-18’ (2018) <http://mofapp.nic.in:8080/economicsurvey/pdf/001-027_Chapter_01_Economic_Survey_2017-18.pdf> accessed 25 October 2020.

Also, the prices of fertilisers, which nowadays have become the sine qua non to agriculture, have also risen over the years (fertilisers cost amounts to around 8% of the total cost20). All this contributes to increase the grain production, but at the same time squeezes out the farmers income. All this with a decline in real investment in agriculture, where the government reduced its already scanty investment in the sector, and this abridged the trade between the farmers and the non-farmers.

So, it can be inferred from the above exposition, that, no doubt that the grain production in the country is reaching its all-time high with every passing season due to the advancement in the agricultural sector and the farming techniques, but the real fruit is still to reach the farmers.

HOW WILL THE NEW BILLS BRING AN UPSURGE IN FARM INCOME?

The moot question still remains, why farm income is not rising even when the production of food grains is hitting the roof with every passing year.

A surplus is not directly proportional to profits.21 Higher profit only occurs when the revenue is more than the cost incurred. In the past few years, the cost of inputs is rising at a higher rate than the cost of output. So, even if the output is rising at a decent rate over the past few years, the cost of input is overshooting the profit margins. So, even if the farmers produce more, their income still remains at a constant level. Conversely, the scope of increasing demand is not just a day task as the national demand is very much dependent on the overall global food grain demand, which is projected to grow at a nominal rate of 1.4% from 2015-2030.22

21. William H Nicholls, “An ‘Agricultural Surplus’ as a factor in economic development” [1963] 71 Journal of Political Economics 1.

22. FAO, ‘Long term perspectives: The outlook for agriculture (2015-2030)’ (2015) <www.fao.org/3/y3557e/y3557e06.htm#:~:text=As%20a%20result%2C%20future%20demand,percent%20for%20the%20next%2030> accessed 27 October 2020.

Technological advancement

However, increasing demand is one of the many factors to increase farm income. The other major contributor to uplift farm income is through altering the market structure. The introduction of online trading, which is facilitated by the current Bill is a significant reform to the present market structure. The effectiveness of technology in the farm sector was witnessed by the ‘Unified Market Platform’ (UMP) in the mandis of Karnataka.23 The use of UMP resulted in increase in the offering price for most of the agricultural commodities so produced. The average increase in the price of 10 commodities (the major ones) was 38% (nominal terms) (and 13% in real terms) which was more compared to any other market in the country.24 The Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020 aims to create such an online market all over the country, which will facilitate trade in the sector. According to the NITI Aayog report on Doubling Farmers’ Income, a 13% rise in crop price will result in a 9.1% increase in farmers' income.25 Therefore, if the price offered to the farmers will rise, it will lead to a rise in an overall increase in farm income. Presently, the government is operating the e-National Agricultural Market (eNAM), which will be strengthened by the passing of this Bill.

Diminishing middlemen influence

Another component to increase the farm income is the market reform to reduce the scope of middlemen and other such costs, thus increasing the profit margin, which in turn will leave the farmer with higher price realisation. This suggestion of the NITI Aayog is very well included in the Bill, which reduces the role of intermediaries to a large extent. Earlier only licensed buyer and traders could trade in the mandis, and therefore, middlemen intervention has to be incurred to make the produce available to the real consumers, which ensured that the real profit goes to the middlemen who buy up the farm products at almost give away prices and sell at outrageous prices to the consumers.26

24. NITI Aayog (n 4).

25. ibid.

26. ON Oguama, VI Nkwocha, “Implication of middlemen in the supply chain of agricultural products” [2010] 10 Journal of Agricultural & Social Research 2.

The license system also created a monopoly in the market which led to cartelisation among the traders in the APMCs, which influenced the price of the commodities. Monopoly is hazardous to a healthy competition which deprives the farmers in this case. The new Bills deals away with the requirement of the licences and culminates the ‘License Raj’. So, now the farmers can get a better price of their crop as the availability of buyers will increase, and the influence of the middle traders will wade away. This model to sell directly to the consumers was adopted by the farmers in Nasik area through a ‘farm to fork’ plan, which led to an increase in their income.27 Another example is Tamil Nadu’s ‘Uzhavar Santhai, ' which directly linked the farmers with the consumers. So, such a step of eliminating the middlemen and ensuring direct procurement is perhaps going to add to the farm income. Now, the farmers’ produce could directly be traded to the buyer, which may include, private corporation, wholesalers, retailers and even B2B trading. Further, through ‘contract farming’, the farmers can get a pre-decided price from the buyers, which will ensure income security to the farmer. The trend of contract farming is expected to rise, where the farmers will get a pre-decided price of the crop and does not have to engage in the market tussle.

Reduction in post-harvest cost

One of the significant costs incurred by farmers was transportation costs. Indian farmers incur a loss of Rs. 92, 651 crores per year in post-harvest losses, primarily including storage and transportation.28 APMCs mandis were not always located at a favourable location. On average, each APMC mandi serves a geographical area of 496 sq. km. against the prescribed limit of 80 sq. km.29 The rising cost of petroleum made the transport of produce from the agricultural land to the mandis even more expensive. This added to the burden of the increased cost of production. As the mandis covered a large area, transportation was a huge burden on the farmers’ pocket, which may be reduced by removing barriers and expanding the ‘trade’ area. Along with the reduction of market fees, the latest Bills aims to abolish transportation costs. As the agricultural sector is being liberalised, it will attract more investment in the sector, which will include investment in the transportation sector by the private entities to lure the farmers into selling their produce.

28. Kiran Pandey, ‘Poor post-harvest storage and transportation facility to cost farmers dearly’ (Down to Earth, 28 August 2018, <www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/poor-post-harvest-storage-transportation-facilities-to-cost-farmers-dearly-61047> accessed 28 October 2020.

29. PRS Legislative Research, ‘Agriculture marketing and role of weekly Gramin Haats’ (21 January 2019), <www.prsindia.org/sites/default/files/parliament_or_policy_pdfs/SCR%20Summary%20-%20Agriculture%20Marketing%20and%20Role%20of%20Weekly%20Gramin%20Haats_0.pdf> accessed 24 October 2020.

Relaxation in stock limits

A breakthrough provided by the amendment to the archaic Essential Commodities Act, 1955, is removing the stock limit on most of the commodities including cereals, pulses, edible oilseeds, etc. except in extraordinary circumstances. Until now, farmers and the traders could not stock up certain commodities above certain stock limits. But, now, as such limitations have been relaxed, traders buying capacity will increase, which will result in more demand and the farmers will be able to sell more and in turn, increase their income. Lack of stock limit will thereby allow the farmers to sell the surplus produce at lucrative prices, and traders can also legally buy in bulk, without engaging in illegal hoarding of stocks.

The Bills are the culmination of various awaited reforms in the agricultural sector, which are being opposed heavily on the stance of Minimum Support Price (‘MSP’). Neither of the Bills mentions about the MSPs that are offered on 24 crops,30 although procurement actually happens for only 2-3 crops including wheat and rice. As the market will now become more competitive, it is unlikely that the private players will offer a price lower than the MSP. The MSP can serve as a base price, and farmers will get a better price for their produce due to the increase in competition. Therefore, the projected increase in competition is expected to result in a rise in farm income.

CONCLUSION

While agriculture’s share in India’s economy has progressively declined to less than 15% due to the high growth rates of the industrial and services sectors mainly after the 1991 reforms, the sector’s importance in India’s economic and social fabric goes well beyond this indicator. The new Bills aims to liberalise the market. It is anticipated that the entry of private players will bring in the much-needed infrastructural investment to the agricultural sector. Much like the 1991 reforms, these reforms aim to rejuvenate the economy by uplifting the lethargic agrarian sector.

The protests over the Bills are generating more heat than light due to the loss of revenue that the state governments would face. However, the agricultural sector is still awaiting the much-desired public investment in improving the input facilities to shrug off a little burden from the shoulders of the farmers. These Bills is expected to bring an increase in competition and would generate more competitive prices for the farmers produce. Although more assistance from the government is required and a watch on the private players is also necessary. If concerted and coordinated efforts are made by the Centre with the States, the new Farm Bills will not only be a boom for the farmers but also for the economy.

- FIR Copy of Mahatma Gandhi assasination case

- Licito Concurso'20

- Rules for Licito Concurso '20- A National Legislative Drafting Competition

- Registration Form for Licito Concurso-20

- www.apexcourtweekly.substack.com

- www.lawupdater.com/wp/

- XIIIth K.K. Luthra Memorial Moot Court Competition 2017

- President of India Presented with the First Copy of the Book Statement of Indian Law Published by Thomson Reuters