|

Introduction

In this age of transnational capitalism, countries and firms are interested in attracting foreign capital because it helps to create liquidity for both the firms stock and the stock market in general. This leads to lower cost of capital for the firm and allows firm to compete more effectively in the global market place. This directly benefits the economy and the country. Availability of foreign capital depends on many firm specific factors other than economic development of the country. Foreign Investment refers to investments made by residents of a country in financial assets and production process of another country. After the opening up of the borders for capital movement these investments have grown in leaps and bounds. But it has had varied effects across the countries. It can affect the factor productivity of the recipient country and can also affect the balance of payments. In developing countries there was a great need of foreign capital, not only to increase their productivity of labor but also helps to build the foreign exchange reserves to meet the trade deficit.

Foreign investment provides a channel through which these countries can have access to foreign capital. It can come in two forms: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI). Foreign direct investment involves in the direct production activity and is of medium to long term nature. But the foreign portfolio investment is a short-term investment mostly in the financial markets and it consists of Foreign Institutional Investment (FII). The FII, given its short-term nature, might have bi-directional causation with the returns of other domestic financial markets like money market, stock market, foreign exchange market, etc. Hence, understanding the determinants of FII is very important for any emerging economy as it would have larger impact on the domestic financial markets in the short run and real impact in the long run.

Significant amounts of capital are flowing from developed world to emerging economies. Positive fundamentals combined with fast growing markets have made India an attractive destination for foreign institutional investors (FIIs). Portfolio investments brought in by FIIs have been the most dynamic source of capital to emerging markets in 1990s. At the same time there is unease over the volatility in foreign institutional investment flows and its impact on the stock market and the Indian economy. The entry of FIIs seems to be a follow up of the recommendation of the Narasimham Committee Report. While recommending their entry, the Committee, however, did not elaborate on the objectives of the suggested policy. The Committee only stated that it would also suggest that the capital market should be gradually opened up to foreign portfolio investments and simultaneously efforts should be initiated to improve the depth of the market by facilitating issue of new types of equities and innovative debt instruments.

Rationale behind FII

Attracting foreign capital appears to be the main reason for opening up of the stock markets to FIIs. The Government of India issued the relevant Guidelines for FII investment on September 14, 1992. Only a few days prior to this, a statement attributed to IFC suggested that India would have to wait for some years before the expected large foreign investment materializes. Regarding the entry of FIIs the then Finance Minister said at a meeting organized by the Royal Institute of International Affairs (London) that the decision to open up the stock market to investments by foreign companies would be good for the country as India needed international capital. He further said that a non-debt creating instrument such as this was superior to raising loans of the classical type so that an unsustainable debt burden was not piled up.

The Finance Minister also said that the liberalization of the economy would bring in international capital of about $10 bn a year rising to $12-13 bn. over the following 2-3 years. A major reason for allowing foreign investment was the economic crisis of 1991. India started having balance of payments problems since 1985, and by the end of 1990, it was in a serious economic crisis. The government was close to default, its central bank had refused new credit and foreign exchange reserves had reduced to the point that India could barely finance three weeks’ worth of imports.

It may also not be a mere coincidence that India decided to open its stock markets to FII investments in the aftermath of the stock scam. The Sensex, BSE Sensitive Index, fell to 2,529 on August 6, 1992 from a high level of 4,467 reached on April 22, 1992. As an incentive, FIIs were allowed lower rates for capital gains tax. This was justified on the basis that this will guard against volatility in fund flows. Thus, the strategy of relying on non-debt creating instruments seems to have yielded results. The flows, however, did not match the initial expectation that capital flows will aggregate US$ 12-13 bn. a year, i.e., nearly US$ 50-60 bn. for the five year period 1993 to 1997. Within portfolio investments, FIIs had a share of nearly 50 per cent and GDRs 44 per cent.

Legal Framework governing FII

In November 1995, SEBI notified the Foreign Institutional Investors Regulations which were largely based on the earlier guidelines issued in 1992. The regulations require FIIs to register with SEBI and to obtain approval from the Reserve Bank of India under the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1973 to enable them to buy and sell securities, open foreign currency and rupee bank accounts and remit and repatriate funds. SEBI’s definition of FIIs presently includes foreign pension funds, mutual funds, charitable/endowment/university funds etc. as well as asset management companies and other money managers operating on their behalf.

For all practical purposes, full convertibility of rupee is applicable to FII investments. Gradually, the scope of FII operations has been expanded by permitting (a) additional categories of investors, (b) recognizing other instruments in which they can invest, and (c) altering the individual and aggregate FII shares in any one Indian company. The latest position is that an FII (investing on its own behalf) or a sub-account can hold up to 10 per cent of paid-up equity capital (PUC) of a company. FIIs can invest in Indian companies through both the portfolio investment route or secondary market purchases and foreign direct investment route. But the policy makes a distinction between portfolio investments by FIIs and foreign direct investment.

Under the portfolio route FIIs can individually acquire up to 10% equity in an Indian company though the aggregate FII limit is pegged at 24%. The limit can, however, be raised after securing board’s approval in sectors where 100% FDI is allowed. The DIPP has now clarified that the same rule will apply if FIIs come through the FDI route. They can not pick up more than 10% stake in a company even if their investments are treated as FDI and that such investment should not be more than 24% of the total equity.

For calculating the FII investment limits, investments made through purchases of GDRs and convertibles are excluded. Investments by NRIs and Overseas Corporate Bodies predominantly controlled by them, which were included earlier, are no longer included for purposes of monitoring the FII investment ceilings. If the company passes the resolutions increasing the limit from 24% to 49%, then only any FIIs can invest money in its shares beyond the limit of 24%. This is interesting, specially when the company management and the promoters can never be interested to allow any outsiders taking a substantial stake in the company, since that puts a lot of pressure on them and restricts their uninterrupted enjoyment of power within the company at the public money, while the investing public remains a silent spectator outside the company, not able to do anything.

A foreign investor can safely adopt the FIPB approval route, if the company management and promoters favour the same. In the light of the above, it is desirable that the Government may amend Foreign Exchange Management (Substantial Acquisition of Shares and Takeover) Rules bringing out consistency in the policies and provisions and providing a level playing field without any discrimination and in the overall interest of the investors. This would not only attract more foreign investment, but improve the level of corporate governance and performance too.

Why Foreign Institutional Investors invest in India?

The FII, given its short-term nature, might have bi-directional causation with the returns of other domestic financial markets like money market, stock market, foreign exchange market, etc. Hence, understanding the determinants of FII is very important for any emerging economy as it would have larger impact on the domestic financial markets in the short run and real impact in the long run. The following is the break up of the various determinants affecting such decision making:

1. Market Size:

Econometric studies comparing a cross section of countries indicate a well established correlation between FII and the size of market (proxied by the size of GDP) as well as some of its characteristics (e.g. average income levels and growth rates). Some studies found GDP growth rate to be a significant explanatory variable, while GDP was not, probably indicating that where the current size of national income is very small, increments may have less relevance to FII decisions than growth performance, as an indicator of market potential.

2. Liberalized Trade Policy:

Whilst across to specific markets – judged by their size and growth is important, domestic market factors are predictability much less relevant in export oriented foreign firms. A range of surveys suggests a widespread perception that ‘open’ economies encourage more foreign investment. One indicator of openness is the relative size of the export sector.

3. Labour Costs and Productivity:

Empirical research has also found relative labour costs to be statistically significant, particularly for foreign investment in labour intensive industries and for export oriented subsidiaries. In India labour market rigidities and relatively high wages in the formal sector have been reported as deterring any significant inflows into the export sector in particular. The decision to invest in china has been heavily influenced by the prevailing low wage rate.

4. Political Scenario:

The ranking of the political risk among FII determinants remains somewhat unclear. Where the host country possesses abundant natural resources, no further incentive may be required, as is seen in politically unstable countries such as Nigeria and Angola, where high returns in the extractive industries seem to have compensated for political instability. In general, so long as the foreign company is confident of being able to operate profitably without undue risk to its capital and personnel, it will continue to invest. Large mining companies, for example, overcome some of the political risks by investing in their own infrastructure maintenance and their own security forces. Moreover, these companies are limited neither by small local markets nor by exchange rate risks since they tend to sell almost exclusively on the international, market at hard currency prices.

5. Infrastructure:

Infrastructure covers many dimensions, ranging from roads, ports, railways and telecommunication systems to institutional development (e.g. accounting, legal services, etc.). Studies in China reveal the extent of transport facilities and the proximity to major ports as having a positive significant effect on the location of FII within the country. Poor infrastructure can be seen, as both, an obstacle and an opportunity for foreign investment. For the majority of the low income countries, it is often cited as one of the major constraints. But foreign investors also point potential for attracting significant FII if host country government permits more substantial foreign participation in the infrastructure sector.

6. Incentives and Operating Conditions:

Most of the empirical evidence supports the notion that specific incentives such as lower taxes have no major impact on FII particularly when they are seen as compensation for continuing comparative disadvantages. On the other hand, removing restrictions and providing good business operating conditions are generally believed to have a positive effect. Further incentives such as granting of equal treatment to foreign investors in relation to local counterparts and the opening up of markets (e.g. air transport, retailing, banking,) have been reported as important factors in encouraging FII flows in India.

7. Disinvestment Policy:

Though privatization has attracted some foreign investment flows in recent years, progress is still slow in majority of low income countries, partly because the divestment of the state assets is a highly political issue. In India for example, organized labour has fiercely resisted privatization or other moves, which threaten existing jobs workers rights. A number of structural problems are constraining the process of privatization. Financial markets in most low income countries are slow to become competitive; they are characterized by the inefficiencies, lack of debt and transparency and the absence of regulatory procedures. They continue to be dominated by government activity and are often protected from competition. Existing stock markets are thin and illiquid and securitized debt is virtually non-existent. An underdeveloped financial sector of this type inhibits privatization and discourages foreign investors.

The main reason why Foreign Institutional Investors put their money in India is because India has the ability to produce goods and provide services at a lower cost. The scarcity of employment opportunities in India has created a situation where industries can easily hire a well qualified or even an over qualified professional at a lower cost, usually at a fraction of international wage standards. In developed countries getting good service from the well qualified professionals can be a significant burden on their budget. Staffing costs affect the profitability and the survival of many foreign companies. If a company does not control their cost then they will probably not survive, especially because their competitors might already be outsourcing in India to save costs.

In India, there are so many qualified people, competing for good jobs. Pay scales provided by foreign companies may be much lower than their domestic rate, but that lower salary will be an excellent one for people in India due to lower living costs and currency exchange rate. If today a single job vacancy is put up, it is common to get a list of 100 candidates, each of them almost equally well qualified. As such the scarcity of employment opportunities brings good competition in the labour force and automatically improves the quality and productivity which is highly favorable for foreign corporations. Labour costs in India rise each year and in some fields like software, it is believed that a double digit salary increase is not possible anymore. This is important to protect the cost benefits and continue to attract Foreign Institutional Investors to India. This is the reason that industries like BPO, IT and Manufacturing are steadily rising in India. There is hardly any big company in the entire world which does not have its presence in India in one way or the other. Some companies outsource their accounting and others outsource IT and BPO operations. Regardless of the domestic issues, they get an excellent service for their money.

In all the hype surrounding China’s emergence as an economic superpower, India can sometimes appear relegated to the sidelines. Yet India, too, is a budding superpower in its own right. Its gross domestic product (GDP) has expanded from £16 billion in 1980 to £500 billion today, and its economy is now the fourth biggest in the world, in terms of purchasing power parity. India’s rapid annual growth rate of more than 7 per cent is reflected in the performance of funds investing in the country. The 30 largest companies in the Mumbai Sensex index increased their earnings at an incredible 35% in their first quarter of this year, blowing away estimates. Revenues jumped 20% and of the 800 publicly-traded companies, average earnings growth is a blistering 17%.

FII and Stock Exchanges

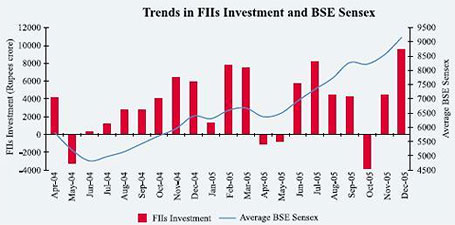

FIIs and Stock Exchanges have an inherent relationship among them. Let us try understanding this with the below mentioned chart which shows trends in the FII investments that have occurred from the period of April, 04 to December, 05. The red bars indicate the FII investments and the blue curvy line indicates the average contribution of the FIIs to BSE Sensex points. The figures at the left indicate the FII investments made where as the figures to the right indicate In April 04 the investments were made thereby moving the FIIs investments graph to 4000 and in the next month they were withdrawn resulting into the negative effect on the Indian stock market. Then since June 04 the investments were made and they have moved in the positive direction there by leading to the positive effect on the stock market. In April and May 2005 the investments were withdrawn and after that the investments were again withdrawn in October 2005.

Let us take another example of the same time period with the market conditions being high oil prices and an environment of rising interest rates. In June and July combined together MFs were sellers to the tune of Rs 2058.15 crore against FIIs’ net purchases of Rs 2866.1 crore, the Sensex gained a smart 5.79%. The same trend can be witnessed in the month of August. FIIs’ net purchases worth Rs 3537.7 crore against MFs’ net buys of Rs 251.46 crore, the Sensex has soared by 8.07%. Another interesting aspect that the data reflects is the growing dominance of FIIs over other set of investors like the mutual funds and retail investors. While MFs purchased shares worth Rs 7573.04 crore in May when FIIs sold stocks worth Rs 8247.2 crore, the markets tanked almost 15%. See the table below (Table 2) which will clearly show the impact FIIs are having on Indian Stock Markets.

| Sensex V/S FII correlation (Table 2) |

Months |

Sensex Gain/ Loss (%) |

FII Net Purchases/Sales (Rs Cr) |

May |

-14.9 |

-8247.2 |

June |

5.34 |

1418.2 |

July |

0.45 |

1447.9 |

August |

8.07 |

3537.7 |

Net FII Sales between May-Aug (2006) |

-1843.4 |

The stock markets in India had to put up the burden in terms of being the second largest loser of foreign money in Asia accounting for 22% of the total net sales, April/May 2006. One of the reasons for the attack of Black Monday is claimed to be FIIs. Statistical records indicated that both FIIs and domestic institutional investors together influenced market sentiment. During the fortnight from May 16 to May 31, 2006, the withdrawals by FIIs were to the extent of US$2.061 billion. This explains the fact that sales of FIIs had a major impact on the market and this impact led to the crash.

A word of caution

India is well placed to attract FII flows over the long term. As economic growth accelerates and tax compliance improves over the next few years, fiscal deficit will come under control. FII flows into India will continue to be strong. India may also get its fair share of inflows by way of increased allocations made to BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries as the group will continue to hold the interest of long-term investors. Corroborating this, the dedicated BRICs Equity Funds, are improving investment inflows. About 43 per cent of the 725 respondents to a survey said they expect to increase their investments in India over the next three years.

However everything is not as picture perfect as it seems. It also is to be noted that Indian stock markets are known to be narrow and shallow in the sense that there are few companies whose shares are actively traded. Thus, although there are more than 4700 companies listed on the stock exchange, the BSE Sensex incorporates just 30 companies, trading in whose shares is seen as indicative of market activity. This shallowness would also mean that the effects of FII activity would be exaggerated by the influence their behaviour has on other retail investors, who, in herd-like fashion tend to follow the FIIs when making their investment decisions.

This feature of Indian stock markets induces a high degree of volatility for four reasons. In as much as an increase in investment by FIIs triggers a sharp price increase, it would provide additional incentives for FII investment and in the first instance encourage further purchases, so that there is a tendency for any correction of price increases unwarranted by price earnings ratios to be delayed. And when the correction begins it would have to be led by an FII pull-out and can take the form of an extremely sharp decline in prices. Secondly, as and when FIIs are attracted to the market by expectations of a price increase that tend to be automatically realized, the inflow of foreign capital can result in an appreciation of the rupee vis-à-vis the dollar. This increases the return earned in foreign exchange, when rupee assets are sold and the revenue converted into dollars. As a result, the investments turn even more attractive triggering an investment spiral that would imply a sharper fall when any correction begins.

Thirdly, the growing realization by the FIIs of the power they wield in what are shallow markets, encourages speculative investment aimed at pushing the market up and choosing an appropriate moment to exit. This implicit manipulation of the market if resorted to often enough would obviously imply a substantial increase in volatility. Finally, in volatile markets, domestic speculators too attempt to manipulate markets in periods of unusually high prices. The Black Monday of 2004 is a constant reminder of the threats FIIs as a group pose in their mad rush to sell. SEBI is supposed to have issued show cause notices to four entities, relating to their activities around Black Monday (May 17, 2004), when the Sensex recorded a steep decline to a low of 4505. These aspects of the market are of significance because financial liberalization has meant that developments in equity markets can have major repercussions elsewhere in the system. With banks allowed to play a greater role in equity markets, any slump in those markets can affect the functioning of parts of the banking system. We only need to recall that the forced closure (through merger with Punjab National Bank) of the Nedungadi Bank was the result of the losses it suffered because of over exposure in the stock market.

On the other hand if FII investments constitute a large share of the equity capital of a financial entity, an FII pull-out, even if driven by development outside the country can have significant implications for the financial health of what is an important institution in the financial sector of this country. Similarly, if any set of developments encourages an unusually high outflow of FII capital from the market, it can impact adversely on the value of the rupee and set of speculation in the currency that can in special circumstances result in a currency crisis. There are now too many instances of such effects worldwide for it be dismissed on the ground that India’s reserves are adequate to manage the situation.

FII and RBI’s Predicament

FIIs are an inevitable part of our liberalization process but, a concern that has constantly arise is that capital flows into India were more in the nature of FII investments rather than FDI and secondly, that the ‘quality’ of the flows needs improvement, implying that there should be greater monitoring and supervision of these flows. Relaxation of capital account controls has enabled cross-border transactions to become easier, and we are seeing significant interest in the secondary market flows. It is important to realize that there are no good funds or bad funds, all are in the market to make money, and they are mobile funds that would move to every market where there is opportunity of making money.

Behind all this is the concern of the RBI over the exchange rate policy and capital account policy. The RBI, quite deservedly, prides itself in steering the country through a very severe foreign exchange crisis in the last decade, through a carefully administered capital account policy and a currency policy. Through capital account controls and a managed exchange rate, the country managed to ride through the tremors of the East Asian crisis fairly smoothly. At the core of the policy is intervention in the exchange rate, which, without any predetermination on the exchange rate as such, enables the RBI to intervene to smoothen the volatility in the currency markets. Coupled with restrictions on capital account convertibility, it has, until now, given the RBI a fairly close control over flows and rates of foreign exchange. It has, therefore, been able to guide monetary policy largely independently of external exchange considerations.Two recent developments have rocked this boat. First, the increasing nature of capital flows, and the inherent weakening of the dollar in the last few years have necessitated repeated interventions in the market to prop up the dollar, and, the RBI does not have enough government bonds left to sterilize the market. Interventions will, therefore, lead to creation of additional liquidity in the market, which is likely to be inflationary.

Thus, the real worry of the RBI is that, first, it will not be able to monitor capital flows, and second that it will not be able to continue its exchange rate policy. There is hardly a country in the world that insists on having all three i.e. a capital account policy, a currency policy, and a monetary policy. China, for example, has decided that it requires external capital flows for employment and economic growth, and has consciously decided to have a fixed exchange rate, and (almost) no monetary policy, and has also decided to weather the inflationary and other problems that the lack of a monetary policy would entail. Other developed countries do not intervene in the exchange rate.

With large foreign exchange reserves, a healthy economy, and openness in the financial architecture, we can only expect the external flows to strengthen. It is time to consider what it is that we want. It is possible to argue that with a large service sector based economy, high savings rate, and low external dependency, we can go back to an era of capital controls. In fact, the RBI is hinting at this. It would be back in the era of exchange permits, and a fixed exchange rate, the economy ring fenced against external shocks, and a monetary policy that is determined by governmental priorities of the day. The other option is to give up management of the capital account, move as much as we want towards convertibility, and most important, give up the exchange rate intervention, and allow the market to determine the rate or, finally, to give up monetary management, and allow international availability of funds to determine the cost of funds.

Finally, there is merit in the view that FDI investment is superior to FII flows. The former is investing in India while the latter is an India investment portfolio. It must be the effort of the Government to change the nature of the flows, and take necessary measures. Improved FDI flows will arise out of transparency, ability to start and close businesses quickly, and the sanctity and quick enforceability of contracts. The written word, in policy, finance or in contracts, must mean what it says. Once the world has this confidence, FDI flows will match and outperform FII investments.

Conclusion

India, which is the second fastest growing economy after China, has lately been a major recipient of foreign institutional investor (FII) funds driven by the strong fundamentals and growth opportunities. Both consumption and investment-led industries linked to domestic demand, such as auto, banking, capital goods, infrastructure and retail, are likely to continue attracting FII funds. FIIs have made net investments of US$ 10 billion in the first six months (April to September) of 2009-10. Major portion of these investments have come through the primary market, more than through buying via secondary markets. At the World Economic Forum at Davos, Switzerland, the Indian authorities strongly advocated the need to regulate capital flows and called for rule-based system of international financial flows. India’s then Finance Minister, Yashwant Sinha had long warned that we can’t allow economies to be destabilized by someone pressing a finger on a computer key and moving billions in and out of markets. If we don’t replace the present chaos with order, then globalization will remain a 13-letter dirty word.

These words could not have had been more prophetic after the Global Meltdown which began in the United States in fall 2007. What is most ironical to note is that the economies which were least regulated and most market oriented were the ones to suffer the worst. India on the other hand despite recession’s dark clouds lingering around it, has been able to manage a decent growth rate and the best part is that inspite of some early sell outs, FIIs have reposed their faith in the fundamentals of Indian economy by reinvesting in India. Thus India even though has certain issues which are to be sorted out but still remains a potent FII attractor and retainer which is generating wealth for everyone concerned. |