Introduction

Education is commonly referred to

as the process of learning and obtaining knowledge at

school, in a form of formal education. However, this

commonplace definition does not go in depth of the need

of education for the all round personality development

of an individual. Education is now recognized as a basic

human right, the need and significance of which has

been emphasized on the common platform of the United

Nations, through the medium of various Covenants and

Treaties. It is also being seen as an instrument of

social change and hence education leads to empowerment

which is very important for a country like India, which

after 59 years of independence has not been able to

eradicate illiteracy in spite of the constitutional

mandate given by way of Article 45 of the Persons with

Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights

& Full Participation) Act, 1995.

Although countries all

over the world have made laws relating to imparting

of education, these laws have not been created in a

vacuum. There exist various international commitments

by way of convention, treaties etc., which have compelled

governments all over the world to enact provisions relating

to education and its establishment as a human right.

Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

1948 clearly proclaims the right to education. Protocol

1 of the European Convention on Human Rights, 1952,

states that no person shall be denied the right to education.

According to UNESCO Convention against Discrimination

in Education,1960, the States’ parties to this

convention undertake to formulate, develop and apply

a national policy which will tend to promote equality

of opportunity and of treatment and in particular to

make primary education free and compulsory.

However, till the mid-1960’s,

the UN recognized the importance of education but did

not make any strong policy recommendation in terms of

making it a fundamental right. It was only after the

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural

Rights, 1966 that the United Nations started viewing

education as a right. Protocol of San Salvador to the

American Convention on Human Rights, 1988, states that

the States’ parties to this Protocol recognize

that in order to achieve the full exercise of the right

to education, primary education should be compulsory

and accessible to all without cost. In 1989, Convention

on the Rights of the Child, the rights of the children

were standardized, in a single legal instrument, approved

by the international community.

In India the development

of right to education has undergone an eventful journey,

when the Constitution was enacted education was kept

in the Part IV of the Constitution, as Directive Principles

of State Policy, wherein Article 41 provides rights

to work, to education, and to public assistance in certain

cases. Article 45 makes provision for free and compulsory

education. Article 46 provides the promotion of educational

and economic interests of scheduled castes, scheduled

tribes and other weaker sections. Education is a two

way concept, it is the state’s obligation to provide

education by way of the Directive Principles of State

Policy, and it is also guaranteed as a fundamental right

in Part IV of the Indian Constitution.

Right to education, was

for the first time recognized as a fundamental right

in the case of Anand Vardhan Chandel v University

of Delhi , the Delhi High Court observed

that the law has now settled that the expression ‘life

and personal liberty’ in Article 21 of the Constitution

includes a variety of rights, though they are not enumerated

in Part III of the Constitution, provided that they

are necessary for the full development of the personality

of the individual and can be included in the various

aspects of the liberty of the individual. The right

to education is, therefore, also included in Article

21 of the Constitution.

In the case of Bapuji

Education Association v State the Court,

expanded the contours of personal liberty guaranteed

by Article 21 of the Constitution to the extent it includes

in its ambit the right of the minorities to education.

But the Supreme Court took notice of this controversy

in the case of Mohini Jain v State of Karnataka

while deciding issues of capitation fee in education

institutions in Karnataka, the court held that the right

to life under Article 21 and the dignity of an individual

couldn’t be assured unless accompanied by the

right to education. The very next year in 1993 the Supreme

Court delivered the judgment in the case of

Unnikrishnan J.P. v State of Andhra Pradesh,

which overruled the decision in Mohini Jain’s

case, wherein, it was held that the right to education

was a fundamental right available to all the citizens

of India but the said right is available only up to

the age of 18 years.

The 86th Amendment Act

was a result of the recommendations of the two committees

namely the Education Commission and Saikia Committee.

The Amendment Act provided for the following three insertions/changes

in the Constitution. The insertion of Article 21-A,

which provides that the State shall provide free and

compulsory education to all children between the ages

of 6-14 years in such a manner as the State may by law

determine. An amendment to Article 45, that is the provision

for early childhood care and education to children below

the age of 6 years; the State shall endeavor to provide

early childhood care and education for all children

until they complete the age of 6 years. In Article 51-A,

after clause (j) the following clause (k) has been inserted:

“a parent or guardian shall provide opportunities

for education to his children or ward between the ages

of 6-14 years.”

Different models of

education of the disabled

In my opinion the Legislature

has completely ignored the children in the age group

of three to six years which is a very crucial period

for mental and physical growth of the child. The new

amendment failed to carry forward the spirit of Article

45 as it stood before the Amendment which provided education

for all children up to the age of 14 years. While it’s

an established fact that the scope and ambit of the

Constitutional provision of right to education extends

to the disabled persons also, the right to education

for the disabled is available up to the age of 18 years.

Disability in The Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities,

Protection of Rights & Full Participation) Act,

1995, has been defined in the interpretation clause.

Disability is not merely

a physical fact, but also involves a normative, cultural,

and legal concept. The society’s perception of

a disabled person also reflects its idea of a normally

functional human being and the definition as considered

by the society gives us an insight into the society’s

self image. The recognition by the society of the terms

mentally and physically disabled also implies a responsibility

of the society towards the people who fit that description.

A society with deep ethos of social responsibility is

likely to be more open in its definition of disability.

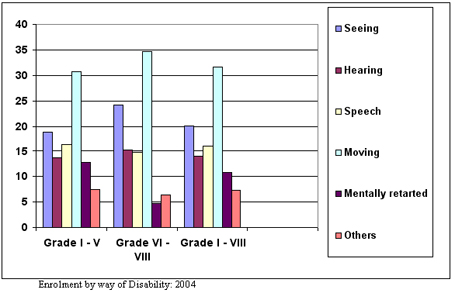

The graph below shows

the distribution of children suffering from various

disabilities in various grades.

(1) Special

Education

The knowledge and processes of educating the disabled

children or ‘special education’ as it is

known now, came to India in the last two decades of

the 19th century through Christian missionaries. While

special education enables the teachers to focus on the

needs disabled children and these special schools are

equipped with the resources that are required as per

the needs of the disabled children. However, the special

education system is based on the principle of segregation

and not integration and is considered to be an expensive

option, and at the same is considered to be violative

of human rights.

In the Indian scenario,

it turns out be an expensive investment and other alternatives

need to be evaluated, analyzed and decided upon soon,

so that the goal of ‘education for all’

is realized as is not cost effective in the rural area

where the infrastructure is not at par with the urban

India. It also leads to the segregation of the disabled

and the same time is also considered to be violative

of the Human Rights as it leads to the formation of

a specific disability culture.

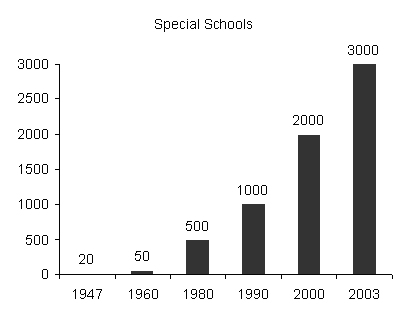

This graph shows that, since 1947, there has been a

steady rise of the number of special schools, which

cater to different kinds of disabilities, which also

indicates that the disabled children who were capable

of being integrated lost the opportunity because the

government did not utilize the funding for building

infrastructure of the mainstream schools so that certain

disabled children capable of being integrated or included

could be admitted in mainstream schools.

(2) Integrated

Education Model. Integrated Education

To overcome the disadvantages omnipresent in the special

model of education, another model of education was developed

in India in mid 1950’s, namely Integrated Education

Model. Integrated Education provides for common education

for all children, whether disabled or non disabled.

In recent years the principle of Integration has been

guidance for reforms in the field of disability care

and special education. It is the goal to help the child

develop such skills and such confident self concept

that are necessary for satisfactory participation in

ordinary social life and work.

(3) Integrated

Education for Disabled Children (IEDC)

The government launched this scheme in December, 1974

to provide educational opportunities to CSWN in regular

schools, to facilitate their retention in the school

system, and to place children from special schools in

common schools.

(4) Projected

Integrated Education for the Disabled (PIED)

The government also launched another scheme and there

was a conscious shift in strategy, from a school based

approach to Composite Area Approach. In this approach,

a cluster, instead of individuals is taken as a project

area. All schools are expected to enroll children with

disabilities. Training programmes were also imparted

to the teachers.

(5) District

Primary Education Programme (DPEP)

This scheme had a powerful impact on the integration

of the disabled children. The main advantage of this

scheme is that it takes care of all the areas identification,

assessment, enrolment, and provision of appliances to

total integration of disabled children in schools with

resource support, teacher training and parental counseling.

(6) Sarv Shiksha

Abhiyan

To uphold its commitments for achieving Education for

All (EFA) by 2010, the Government of India had launched

Sarv Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) IN 2000-2001. Sarv Shiksha

Abhiyan gives prime importance to good quality education

to all children including those with disabilities. It

has a special mandate to serve children with disabilities

at the district level. The scheme has a provision that

Rs.1200 to be spent on every child with disability identified

with the district.

(7) Inclusive

Education

The inclusive model of education is another model of

education utilized for the education of the disabled.

In inclusive education, the disabled children are taught

in general education classrooms, in mainstream schools

alongside children of their age who do not suffer from

disabilities. This system of education ensures that

the disabled children are not segregated at any stage

and helps them to develop a sense of worth, standing

and belonging in society. It also enables sensitization

of children who are not disabled and helps to form a

disabled friendly society which is impossible in the

special education system setup.

Legislative Provisions

pertaining to the Law of Disability

The 1989 United Nation

Convention on the Rights of Child states that disabled

children have the “right to achieve participation

in the community and their education should lead to

the fullest possible social integration and emotional

development.”The 1990 World Conference on Education

for All: Meeting Basic Learning Needs states that the

learning needs of the disabled demand special attention.

The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on

Special needs Education (1994) stipulates that disabled

children should attend neighborhood school. It declares

that regular schools with this inclusive orientation

are the most effective means of combating discriminatory

attitudes, creating welcoming communities, building

an inclusive society and achieving education for all.

India has been a signatory to all these declarations.

The year 1981 was very

significant being the International Year for Disabled

Persons (IYDP). It was also in this year, in India that

the education of the disabled was considered to be as

a human resource development. Prior to this the education

of the disabled, which was catered to largely in special

schools, came under the purview of Department of Social

welfare. This shift was considered significant because

it helped create awareness in the general education

system that disabled persons are also “human resources”

and can become contributing members of the society.

In the 1990’s two

historical legislation were enacted namely the Rehabilitation

Council of India Act, 1992 passed in Parliament was

created by the Ministry of Welfare to regulate manpower

development programmes in the field of education of

children with special needs and The Persons with Disabilities

(Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full

Participation) Act, 1995.

In spite of the disadvantages

of the special schools and the impact on the lives of

the disabled children studying in them, the law still

provides for setting up of these schools for disabled

children. Special schools have steadily been increasing.

Presently there are about 3000 special schools addressing

persons with different disabilities. It is estimated

that there are 900 schools for the hearing impaired,

400 schools for the visually impaired, 1,000 for the

mentally retarded and 700 for the physically disabled

children.

Conclusion and Suggestions

Keeping in mind, the developments

that have taken place in the last two decades, in the

field of education of the disabled, it is clear that

to fulfill the goal of Education for All there has to

be constant monitoring of children with special needs

and disabilities. Because of the advent of special education,

and the segregation, thereof, the general population

is not exposed to the disabled people and don’t

know how to react. If the law still calls for segregation

of the disabled people, the people in the mainstream

society do not get an opportunity to interact with these

people and therefore are not sensitized to their needs.

If we, as a society are exposed to disabled people,

from the very inception and interact with them, the

phenomena of de-labeling will also gain strength.

The law as it stands today

does not make differentiation in the education of the

slightly, moderately and severely handicapped children

and therefore, disabled children who could have been

integrated in the mainstream schools are denied the

opportunity because the Legislature has failed to distinguish

between the needs and requirement of the children suffering

from slight, moderate and severe disability. Integrated

and Inclusive model of education needs to be applied

keeping in mind as to what is more suitable in the given

infrastructure and economic conditions prevailing in

the area.

Education and agriculture

are the two sectors, often referred to as agronomy,

which can help steer a country on the path of development.

Therefore special attention needs to be placed on developing

these two sectors. In India the education policy has

lacked foresight and vision, and whenever problems have

arisen, rather than tackling the problem, the authorities

have seen fit to the change the policy to suit the circumstances.

There are a few

suggestions that should be carried out so that the integration

of the disabled children in the education field is ensured

like providing emphasis on integration, facilities for

training teachers and enforcing a systematic education

policy of the state in order to guarantee the disabled

people their fundamental right to education.

_________________________________________________________________

K.S. BAGGA is an Advocate with Bagga

and Associates at New Delhi, India. |